Are We Repeating 2000

Ann Yiming Yang

1/9/20263 min read

The Dot-Com Bubble vs. Today’s AI-Driven Market

In 2000, the tech industry learned a brutal lesson: transformational technology does not guarantee sustainable valuations.

The dot-com era was driven by a real breakthrough: the internet, but capital raced ahead of fundamentals. When confidence cracked, the collapse was swift and indiscriminate.

Today, as investors whisper about a potential “2026 reckoning,” the comparison has resurfaced. This time, the technology is AI.

The question isn’t whether AI is real.

It’s whether the pricing of AI is.

A quick recap: what actually happened in 2000

The setup

Internet adoption exploded.

Venture capital flooded the market.

Companies went public with minimal revenue, or none at all.

Valuations were justified by narratives: eyeballs, first-mover advantage, land grab.

The peak

The NASDAQ Composite rose ~5× from 1995 to March 2000.

IPOs doubled on day one despite weak fundamentals.

The crash

Rising interest rates and missed growth expectations shattered confidence.

NASDAQ fell ~78% from peak to trough.

Thousands of startups failed.

Survivors existed, but they were rare.

The internet didn’t fail.

Pricing failed.

Today feels uncomfortably familiar

Similarity #1: A real technological revolution

Then: the internet changed everything.

Now: AI is reshaping software, labor, and capital allocation.

Both are genuine paradigm shifts.

Similarity #2: Narrative-driven valuations

Dot-com era: “We’ll monetize later.”

AI era: “Scale first, profits later.”

In both periods, future dominance is priced into today’s valuation.

Similarity #3: Capital intensity & burn

Many AI companies require massive ongoing compute spend.

Revenue growth does not always scale as fast as infrastructure costs.

This is a structural risk, not hype.

Similarity #4: Concentration risk

In 2000, capital crowded into “internet everything.”

Today, capital crowds into a narrow set of AI leaders and suppliers.

When expectations slip, concentration amplifies downside.

The most important differences

Difference #1: Today’s leaders have real revenue

Many current AI leaders generate billions in annual revenue.

In 2000, many companies had none.

Difference #2: Infrastructure vs. websites

AI platforms are closer to cloud infrastructure than marketing sites.

If they succeed, they become deeply embedded, not optional.

Difference #3: Fewer companies, larger stakes

The dot-com bubble had thousands of public names.

Today’s risk is concentrated in far fewer, much larger entities.

This means fewer bankruptcies, but potentially larger valuation resets.

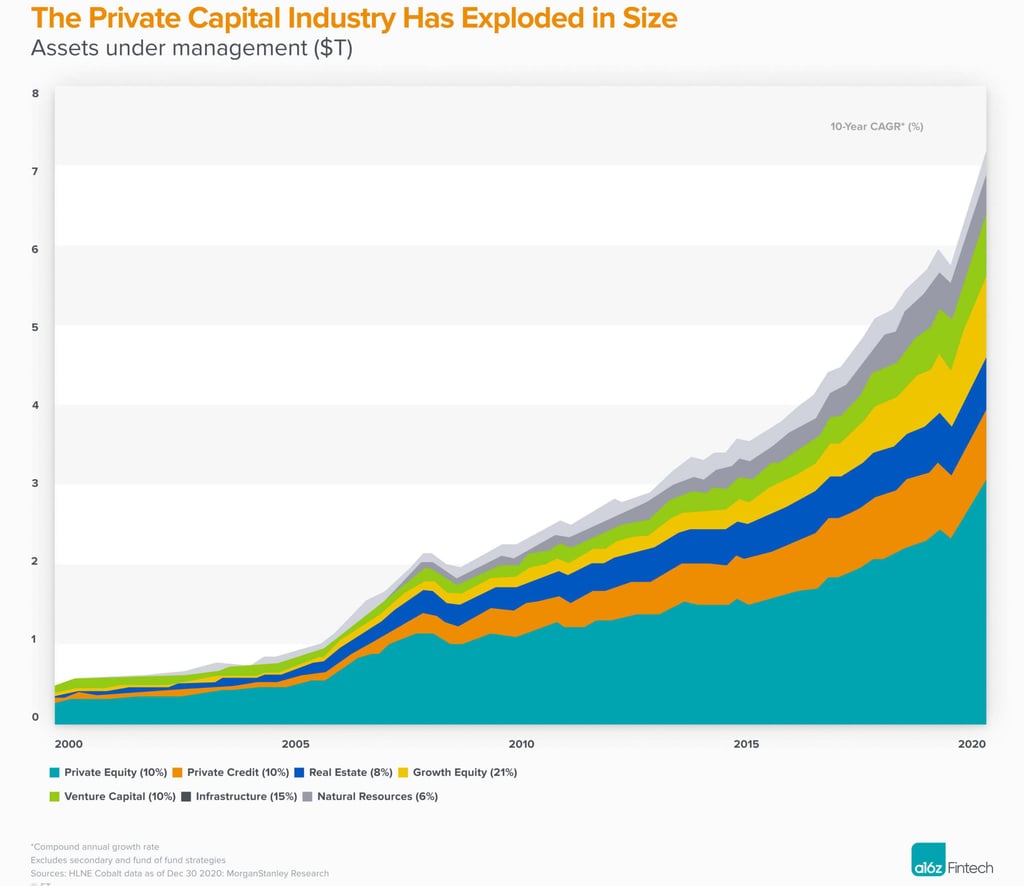

The private-market pressure cooker

One major difference from 2000 is where the risk sits.

In 2000, excess risk lived in public markets.

Today, much of it lives in private markets.

Large private companies face:

Massive capital needs

Limited private-market liquidity

Pressure from employees and early investors for exits

This creates incentives to:

IPO earlier

Cut costs aggressively

Reprice expectations quickly if markets tighten

That’s where fears of layoffs and “sudden discipline” come from.

If a “2000-style moment” happens, what would it look like?

It likely would not look like:

AI disappearing

All major players collapsing

Technology progress stopping

It would look like:

Valuation compression

Hiring freezes and layoffs

IPO windows closing abruptly

A sharp divide between durable platforms and speculative layers

In other words:

the market gets serious.

The real lesson from 2000

Every cycle repeats the same mistake: confusing technological inevitability with financial inevitability.

AI may be inevitable.

But who wins, at what price, and on what timeline is not.

That distinction is what markets tend to relearn the hard way.

The internet was real in 2000.

AI is real today.

The danger has never been the technology; it’s always been the valuation.